One hundred years ago, Jacques Ledoux was born. This autumn, we pay tribute to the man who shaped CINEMATEK to become both an institution that cannot be ignored at the international level, as well as a place of exchange where, every day, the adventure of the 7th art is carefully exhibited in the widest possible spectrum.

From the softest steel: Jacques Ledoux, pioneer and architect of the Belgian film archive

To mark the centenary of Jacques Ledoux’s birth, CINEMATEK is devoting an exhibition to the illustrious first curator of the institute. Author and film teacher Anke Brouwers has written a reflection on the exhibition to mark this 100th anniversary.

It seems only fitting to highlight Ledoux’s life story and achievements, since his enthusiasm, dedication, passion and perseverance have made the Belgian film archive an international reference. Yet at first sight, an exhibition named after and built entirely around Jacques Ledoux seems to clash a little with the extremely private person the man has always been - he never spoke about his private life - but Ledoux did seize every opportunity to make his work known to the world, so the exhibition also focuses emphatically on his achievements and not on the man himself. The result is the presentation of a life’s work.

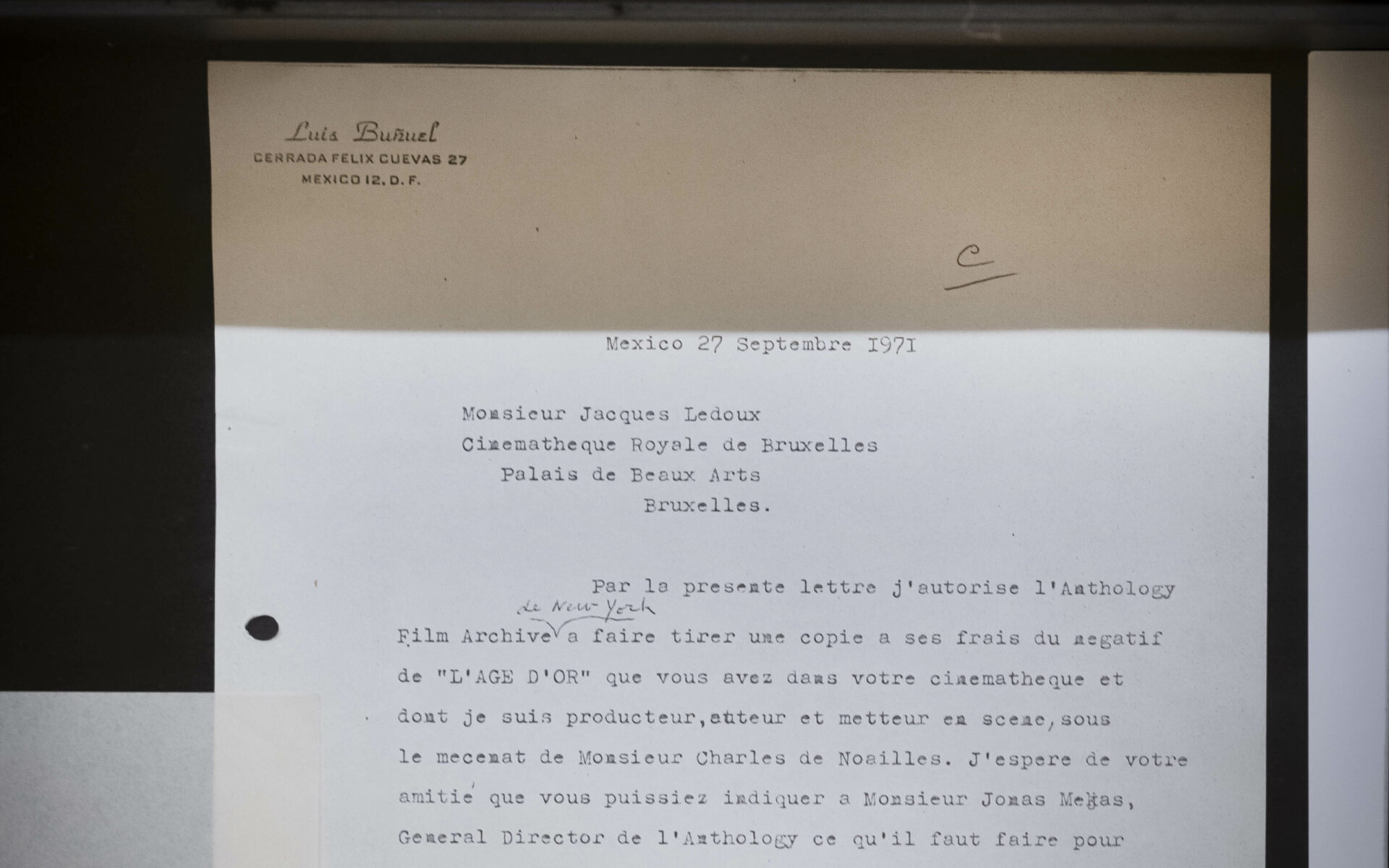

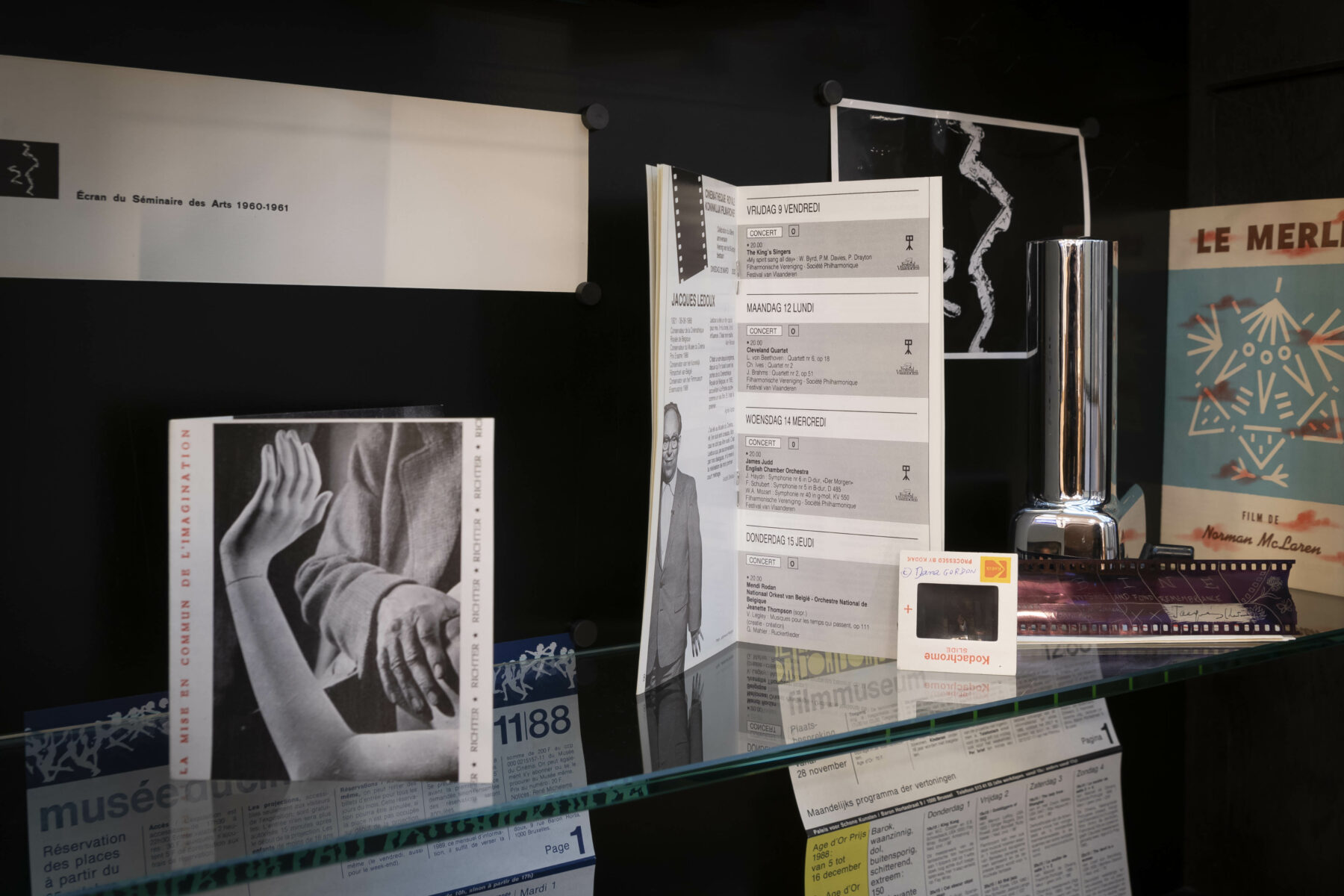

Ledoux’s importance for the current CINEMATEK and for film conservation in general is revealed through a series of objects, reference books, brochures, notes, telegrams, letters, photos, posters and film footage which highlight both the milestones and the patient fieldwork and study. Through sketches and small notes, we learn how what were at first only plans and ideas were soon transformed into statutes, foundations and concrete initiatives. Postcards, telegrams and (illustrated) letters from Marguerite Duras, Federico Fellini, Chris Marker, Agnès Varda, Robert Aldrich and from almost every filmmaker of the Nouvelle Vague/Cahiers du Cinéma generation illustrate his personal relationship with international filmmakers. His support for their work and oeuvre earned them gratitude and often friendship too. For example, Ledoux is expressly thanked in the commissioning of books by P. Adams Sitney (historian of avant-garde cinema) and Martin Scorsese (Scorsese on Scorsese).

Ledoux’s figure is interwoven with the history of the archive, but also with film history itself.

He opened up the collection to film-makers for study purposes (when Truffaut was preparing his book on Hitchcock, he came to Brussels to study the film-maker’s work) or to satisfy their cinephile hunger (what Godard could not see in Paris, he saw during a city trip to Brussels). But Ledoux also helped makers to obtain copies of their own work.

Today, we think it is normal to be able to get legal or illegal films with a few clicks of the mouse, but we often forget that this availability is thanks to pioneers such as Ledoux (and of course Iris Barry, Henri Langlois, Jerzy Toeplitz, Ernest Lindgren, ... and the many private collectors) who realised that collecting, preserving, possibly copying and if possible restoring were essential for the film heritage. They had known for a long time that nitrate is not patient.

A letter from Buñuel in the exhibition is a remarkable example of this: he asked Ledoux in 1971 to make a negative of his film L'Âge d'or (1930) for the Anthology Film Archives (an international centre for the preservation, access and study of mainly experimental or avant-garde film) established by Jonas Mekas.

Romantic

The exhibition is structured chronologically and thematically. We get an insight into Ledoux’s earliest cinephile activities, such as his involvement with the film club Camera Obscura, with the founding of a film magazine, Travelling, or with film screenings in Brussels. From 1949, he became the curator of the film archive, which in 1962 received the designation ’royal’ (apparently this was no special merit, it happened automatically.) Ledoux was once described by a critic as a ’romantic curator’: he was aware that film material is vulnerable and that death and decay are ingrained in the medium, but this should not lead to the artifacts being buried alive (in tombs/film cans). In other words, the films also had to be experienced and felt by an audience. He did not care about perfectly preserved and protected film copies, locked up in the collector’s bunker. Of course, only those copies whose condition was deemed to be non-precarious could be shown.

An overview of the programmes that have been shown in the Brussels Film Museum over the years makes your mouth water. In the year I was born, you could go and see a retrospective of Nicholas Ray and Jean Gabin (so it is not surprising that I started to love cinema). In 1971, the Film Museum anticipated our contemporary obsession with (super)heroes in a programme entitled ’Superheroes Past and Present’.

And already in 1968 an entire month was dedicated exclusively to films by female filmmakers (les femmes derrière la caméra). Throughout the years, the programming of the film museum was broad, inclusive, surprising, diverse. Although Ledoux was assisted in the programming from the 1970s by, among others, (the later curator) Gabrielle Claes, he remained closely involved. In 1988, for example, he personally collected the Indian film-maker Satyajit Ray at the airport, bringing along a Tintin comic book for his son.

Besides being a place to experience film history and culture, the film archive also became a place where film publications, posters, photos and documentation could be consulted, in other words, a place for deepening and study. Perhaps the most beautiful thing of all, and something that is envied even abroad, was the small hall that he opened to show silent films on at the time a daily basis with live piano accompaniment. (A charming booklet was recently published by CINEMATEK in which house pianist Fernand Schirren reveals the secret of good film accompaniment. The naughty answer has something to do with the tactile...)

Photographs of FIAF conferences and a very special letter by cineastes of the Nouvelle Vague to Ledoux

Mythical

In addition to his role in the FIAF (Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film) as secretary general (for 17 years), his tireless work as curator of the archives (for 40 years), his zeal for a broader platform for animated film, his work as a programmer for the film museum, the further development of the collection (since 1938 the film library has collected 71 857 titles), Ledoux also created three important long-term initiatives: The L’Âge d’or Prize, Film Finds (Cinédécouverts) and decentralisation.

With the L’Âge d’or Prize, he wanted to give a chance to courageous, inquisitive, experimenting film makers, who dared to deviate from well-trodden paths. Key words were poetic, subversive and original. The name of the prize was of course significant; after all, for Ledoux, Buñuel’s film of the same name was a reference point for the kind of formally and intrinsically perverse or playful cinema that the prize was intended to reward. Critical examination of the medium was thus encouraged, and in this way the film archive was also actively involved in the cinema of the present, not only focusing on the preservation of the past, but also a facilitator, perhaps even an inspirer, for contemporary cinema. (One of the most direct contributions to film history is the film celluloid by Gevaert that Ledoux donated to the budding American film maker Martin Scorsese).

Filmvondsten (since 1979), on the other hand, focused on younger and more international talent and aimed to enable the distribution of valuable unpublished films. Thanks to the creation of the decentralisation of classic and contemporary films (a collection of films from the archive whose rights were arranged by the film library), it became possible for schools, cinemas, film clubs and cultural institutions to show film classics and also some more obscure titles on pellicule at an affordable price. (Since 2020, the decentralisation is quasi-completely digital and web platforms can also show films from the collection). Finally, the festival of experimental film, EXPRMNTL, should not go unmentioned. Between 1949 and 1974, five editions of the festival took place between Christmas and New Year in the casino of Knokke-Le-Zoute. In that period, the fashionable location could be occupied by then-young filmmakers such as Peter Kubelka, Stan Brakhage, Walerian Borowczyk, Agnès Varda, Bruce Conner and Kenneth Anger. In 2017, Brecht Debackere made a documentary about this festival, which has rightly acquired a mythical aura after all these years.

Lists

We also learn that Ledoux was a passionate ’list man’ (the many cards in the exhibition show that he liked to jot down thoughts, bullet points, step-by-step plans): he made lists of the points he wanted to achieve as president of the FIAF, lists of films he wanted to see, lists of films he wanted to programme, lists of the best films of all time (according to others), lists of the most underrated films of all time (according to others) and on the basis of existing lists he made even more lists (by title, by director, by country, by theme...)

He himself has always refused to make a list of his favourite films (a reticence that was certainly appropriate), and only in 1988 did he make a selection of ’flamboyant films’ at the request of his friend Huub Bals, the then director of the Rotterdam International Film Festival. This selection of hot-blooded films will be screened at CINEMATEK in the coming months. Fiery Italian diva cinema such as the aptly titled Il Fuoco (Pastrone 1915) will be shown alongside Freaks, the maverick of the MGM studio (by Tod Browning, 1932), Caniche by Bigas Luna (a L’âge d’or laureate in 1981), Female Trouble (a 1974 camp melodrama by John Waters), Foolish Wives (immoral moral lessons by the ever irreverent Von Stroheim from 1922), all films that in their own way can be called baroque, ostentatious, sensual, intense, wanton, brutal, opulent or overloaded. In short: flamboyant.

Christophe Piette, the curator of the exhibition, has smuggled a few details into the exhibition which discreetly and respectfully hint at Ledoux, such as the soap dispensers which he had installed in the toilets of the old film museum (after his alert eye had noticed these elegant utensils during a trip to Germany) or a photo in which he can be seen with one of his other passions: the puppet.There is also a tin film box in which a reel of Nanook of The North (Flaherty 1921) was kept, so that we cannot help but think back to the well-known story of how a young Ledoux, while living in hiding during the Second World War, ’found’ a copy of the film in his hiding place. (’Found’ I write in inverted commas because it has since transpired that Ledoux did not just find the film but actually bought it in Brussels. It is true that in the monastery where he lived in hiding for a long time he had a 16 mm projector at his disposal and could therefore watch films there). This film discovery sealed his further life as a saviour and knight of the seventh art. It is a personal story, of course, but its symbolism transcends the private and the concrete.

Of course, the life’s work that the exhibition so lovingly displays must also (perhaps primarily) be experienced in the film room itself. The real legacy of Ledoux is the impressive collection of preserved films, and also and even especially the smaller films, the experimental films, the ugly ducklings, the cult classics, the films made by women and minorities. The realisation that access to (classic) films from all over the world, from the whole history of film, is a privilege for which people have lived and fought passionately: it should make us quiet at every screening.

Until February 2022, CINEMATEK will commemorate Ledoux through the exhibition and various film screenings and lectures.

On 26 October, Jacques Ledoux’s birthday, a screening of La Jetée (Marker 1963) is planned.

About the author:

Anke Brouwers (1980) is an author and film professor at the School of Arts/HoGent.

Hardcover catalogue published on the occasion of what would have been the hundredth birthday of Jacques Ledoux (CINEMATEK, Brussels 2021)119 pages / Illustrations in colour and black and white / All texts in French, Dutch or English

The book Jacques Ledoux brings together exclusive testimonies collected in 2021 from historians such as David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson or Bernard Eisenschitz and former staff members of the Film Archive. A testimony by Paul Davay and a transcription of an interview with Jacques Ledoux, both previously unpublished, complete this work, along with the republication of a biographical note by Gabrielle Claes. The book is richly illustrated with archival images. The publication is on sale at 15€ in our webshop.